Absinthe

Absinthe (from the French) is a distilled spirit derived from herbs including the flowers and leaves of wormwood, Artemisia absinthium.

Absinthe is known for its popularity in France — and especially its romantic associations with Parisian artists and writers—in the late 19th century and early 20th century , until its prohibition in 1915. The most popular brand of absinthe known to the world was Pernod Fils.

Absinthe usually has a pale-green peridot color (giving it its nickname "The Green Fairy") and tastes much like an anise-flavored liqueur, but with a more subtle flavor due to the many herbs used, and light bitter undertones. Unlike a liqueur, it is not pre-sweetened. In addition to wormwood, it contains anise (often partially substituted with star anise), Florence fennel, hyssop, Lemon balm (melissa), and Roman wormwood (Artemisia pontica). Various recipes also include angelica root, calamus (sweet flag), dittany leaves, coriander seed (spice), and other mountain herbs.

A simple maceration of wormwood without distillation produces an extremely bitter drink, due to the presence of the water-soluble absinthin, one of the most bitter substances known. Authentic recipes call for distillation after the primary maceration and before the secondary or "coloring" maceration. The distillation of wormwood, anise, and florence fennel first produces a colorless "alcoholate", and to this the well-known green color of the beverage is imparted by steeping with the leaves of roman wormwood, hyssop, and melissa.

Inferior varieties are made by means of essences or oils cold-mixed in alcohol, the distillation process being omitted.

The alcohol content is extremely high (45 percent - 90 percent), given the low solubility of many of the herbal components in alcohol. It is usually not drunk "straight," but consumed after a fairly elaborate ritual in which a specially designed, trowel-shaped, slotted spoon is placed over a glass, a sugar cube placed on the spoon, and water very slowly poured over the sugar until the drink is diluted 3:1 to 5:1. During that ritual, the components that are not soluble in water come out of solution and cloud the drink; that milky opalescence has always been called the "louche".

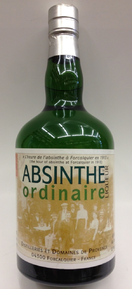

Historically, there were four varieties of absinthe: ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, and supérieures or Swiss, the latter of which was of a higher alcoholic strength than the former. It can be colored green (which is done to add flavors) or left clear. The best absinthes contain 65 percent to 75 percent alcohol. It is said to improve very materially by storage. It is known that in the 19th century absinthe, like much food and drink of the time, was occasionally adulterated by profiteers with copper, zinc, indigo, or other dye-stuffs to impart the green color, but this was never done by the best distilleries.

Polemic

It was thought that excessive absinthe-drinking led to effects which were specifically worse than those associated with over-indulgence in other forms of alcohol -- which is bound to have been true for some of the less scrupulously adulterated products, creating the condition absinthisme. Undistilled wormwood essential oil contains a substance called thujone, which is an epileptic (and can cause renal failure) in extremely high doses, and the supposed ill effects of the drink were blamed on that substance in 19th century studies.

More recent studies have shown that very little of the thujone present in absinthe actually makes it into a properly distilled absinthe, even one re-created using historical recipes and methods, so much so that a recent French distiller has had to add pure wormwood essential oil to make a "high-thujone" variant of his product to cater to a different market. It can remain in higher amounts in oils produced by other methods than distillation, or when wormwood is macerated and the macerate not distilled, especially when the plant stems are used, where thujone content is the highest.

A study in the "Journal of studies on Alcohol" concluded that a high dose of thujone in alcohol has negative effects on attention performance. It slowed down reaction time and subjects concentrated their attention in the central field of vision. Medium doses didn't produce a noticeable effect from plain alcohol. The high dose of thujone was larger than what one can get from current "High thujone" absinthe before becoming too drunk to notice and most people describe the effects of absinthe as a more lucid and aware drunk. This suggests that thujone alone is not the cause of these effects.

The non-French spelling of "Absinth" has been adopted for wormwood-based drinks produced in Central Europe (since the beginning of the 1990s). These products bear very little resemblance to absinthe (with an 'e'): they are usually bitter and contain little anise, but are marketed to ride the coat-tails of the historical French product's romantic associations and psycho-active reputation.

Typically, the low herbal content of these drinks means that they do not "louche." As thujone is still associated with the myth of absinthe as a psycho-active drink, many of them are touted to have "higher thujone content." A separate, more dramatic, and potentially very hazardous "fire" ritual was invented for those drinks by a Czech manufacturer, in which the sugar cube is drenched in absinth then set on fire, and less water is added (presumably to maximize the very real psycho-active effects of the alcohol).

Legal status

After publicity about several violent crimes supposedly committed under the direct influence of the drink, along with a general tendency toward hard liquor consumption due to the French wine shortage in France during the 1880s and 1890s, the temperance leagues and winemaker's associations effectively targeted absinthe's popularity as social menace. They said that it makes people crazy and criminal, it turns men into brutes and threatens the future of our times. Edgar Degas' 1876 painting, L'absinthe (The Absinthe Drinkers) (now at the Mus%E9e d%27Orsay) epitomized the popular view of absinthe "addicts" as sodden and benumbed and Emile Zola described their serious intoxication in his novel L'Assommoir. Absinthe was banned from sale and production in most countries by 1915.

The prohibition of absinthe in France led to the growing popularity of pastis, another aniseed-flavored liquor that did not use wormwood.

France never repealed the 1915 law, but in 1988, a law was passed to clarify that only beverages that do not comply with European Union regulations with respect to thujone content, or beverages that call themselves "absinthe" explicitly, fall under that law. This has resulted in the re-emergence of French absinthes, now labeled "spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe." Interestingly, as the 1915 law regulates only the sales of "absinthe" in France but not its production, some of these manufacturers also produce variants destined for exports plainly labeled "absinthe." It is of a lower alcohol content (40%) and is most notably produced in the distilleries of Provence after the wormwood harvest and also in Doubs and in Fougerolles. The wormwood used has been bred to limit the thujone to 10%.

In the 1990s an importer realized that there was no United Kingdom law about its sale (it was never banned there) - other than the standard regulations governing alcoholic beverages - and it became available again in the UK for the first time in nearly a century (though with a prohibitively high tax reflecting the high ethanol content). It had also never been banned in Spain or Portugal, where it continues to be made. Recent European Union laws have allowed absinthe and absinthe-like liquors to once again be made commercially; however, regulations place strict controls on the thujone level.

In the Netherlands a law dating from 1909 prohibited the selling and drinking of absinthe, but this law was successfully challenged by Amsterdam wineseller Menno Boorsma in July 2004, making absinthe once more legal. However, the prosecutor appealed and there will be a second trial in a higher court.

United States

According to the United States Customs office, "The importation of Absinthe and any other liquors or liqueurs that contain Artemisia absinthium is prohibited.".

The prevailing consensus of interpretation of United States law among American absinthe connoisseurs is that:

- It is probably illegal to sell items meant for human consumption which contain thujone derived from artemisia plant species. This derives from an FDA regulation.

- It is probably illegal for someone outside the country to sell such a product to a citizen living in the US, given that customs regulations specifically forbid the importation of "absinthe."

- It is probably not illegal to purchase such a product for personal use in the US.

- Absinthe can be and occasionally is seized by United States Customs, if it appears to be for human consumption.

An absinthe-like liqueur called Absente, made with Artemisia abrotanum instead of Artemisia absinthium, is claimed by the importers to be sold legally in the United States; however, the FDA prohibition extends to all Artemisia species, including even, in theory, Artemisia dracunculus, known as tarragon. However, Absente has been spotted on the shelf in US retail liquor stores.

External links

- Information

- Oxygenee's Absinthiana - The Virtual Absinthe Museum: History, Absinthe Antiques and Art, The most comprehensive Absinthe FAQ on the web

- Absinthe: The Green Goddess by Aleister Crowley

- Feeverte.net Forums, reviews and information

- Article on Absinthe from the British Medical Journal

- Absinthe Information, Reviews and Forum

- Absinthe FAQ

- Ritual videos